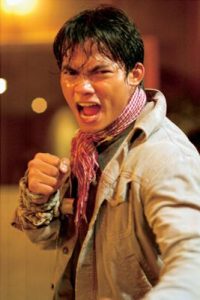

About a year ago I asked Tony Jaa how he developed his leaping abilities, and he simply said, “Flower and leaf.” Initially I thought it was perhaps a metaphor for the jungle community he was raised in, an appreciation for nature that saw him using trees, vines and deep forest paths for training. I guess I imagined the likes of Sabu, the famous actor from India who was labeled “The Elephant Boy” by Hollywood for his jungle films in which he was one with the animals. Interestingly, Sabu and Jaa almost look like brothers. As it turns out, I was not far off. Jaa told me that during his childhood he was raised in a jungle-village that was in a Red zone, an area near the Cambodian border where he would daily hear wartime bombers unleashing their load. He recalled having to run for cover. But what also made those tumultuous times more bearable were the moments he spent with his two pet elephants Flower and Leaf. Every day from the time they were babies and Jaa was a child, Jaa would take these pachyderms down to the river and leap up onto their backs and dive into the water. He did this every day for many years, so as the elephants grew, so did Jaa and his leg strength. Now, cinematically, his childhood experience has come full circle, serving as impetus for his latest film TOM YUM GOONG (to be released by The Weinstein Company as THE PROTECTOR). The film thematically centers on his love for elephants.

About a year ago I asked Tony Jaa how he developed his leaping abilities, and he simply said, “Flower and leaf.” Initially I thought it was perhaps a metaphor for the jungle community he was raised in, an appreciation for nature that saw him using trees, vines and deep forest paths for training. I guess I imagined the likes of Sabu, the famous actor from India who was labeled “The Elephant Boy” by Hollywood for his jungle films in which he was one with the animals. Interestingly, Sabu and Jaa almost look like brothers. As it turns out, I was not far off. Jaa told me that during his childhood he was raised in a jungle-village that was in a Red zone, an area near the Cambodian border where he would daily hear wartime bombers unleashing their load. He recalled having to run for cover. But what also made those tumultuous times more bearable were the moments he spent with his two pet elephants Flower and Leaf. Every day from the time they were babies and Jaa was a child, Jaa would take these pachyderms down to the river and leap up onto their backs and dive into the water. He did this every day for many years, so as the elephants grew, so did Jaa and his leg strength. Now, cinematically, his childhood experience has come full circle, serving as impetus for his latest film TOM YUM GOONG (to be released by The Weinstein Company as THE PROTECTOR). The film thematically centers on his love for elephants.

“As a kid, I always played with elephants,” Jaa shares with me. “You learn to become in harmony with the elephants; they’re not just pets, but become part of the family. It takes great skill to ride them and to watch them pick up water and throw it over their back; you just can’t help but to feel one with them. Now with this film, I finally have the chance to share this, my passion for elephants, with the film audience. One of my goals is to open an elephant sanctuary for abandoned elephants.”

It is with this spirit that Jaa and Thailand’s TV-ad director whiz-kid Prachya Pinkaew set out to use martial arts and THE PROTECTOR to subliminally show the plight of elephants in Thailand.

It is a sad irony that a creature so revered as an object of Thai cultural and historical pride should suffer so terribly behind the public curtain.

Historically, elephants in Thailand were held in high esteem, as evidenced by their depictions as battle elephants. They have been vividly portrayed in art and cinema as towering creatures with Siam’s greatest leaders riding atop them, charging into battle against Burmese invaders. In fact, there is a scene in THE PROTECTOR where a painting comes alive to show a certain aspect of one such battle, which serves as the impetus for the film’s fights: the Jaturungkabart soldiers.

“The Jaturung warriors are the guardians of the four feet of the elephant that the King rides on,” Jaa explains. “They were awesome fighters and excelled in the use of the shield, sword, martial arts in general and Muay Boran. It was their sole responsibility to prevent the enemy from harming the elephant’s feet, because if the feet are injured, the King falls, dies, battle over. Their fighting techniques used broad sweeping attacks and wide circular slashing maneuvers.”

To Westerners, Thai martial arts is Thai kickboxing. Yet Muay Thai is not a martial art but a sport that has been around since 1930, its techniques being a watered-down version of the lethal martial art Muay Boran. Muay Boran comes from an even older version of Pahuyuth (systems of Thai martial arts), called Ling Lom (air monkey), which has its foundations in Krabi-Krabong. Although the ancient forms of Muay Thai are Buddhist in nature, the Ling Lom aspect of Muay Boran has its foundation in the monkey god Hanuman, from the Hindu legend of Ramayana, where the fights were really re-enactments of the battling deities.

“The fights in THE PROTECTOR are more aggressive than in ONG BAK,” Jaa says as he begins to demonstrate certain hand and arm postures, “and in this film I used elements of the elephant combined with Muay Thai and other martial arts. With the elephant aspects I tried to reflect how the elephant catches, throws and breaks things, similar to what an elephant would do to tree with its trunk and feet. For example, there is a move in ancient Muay Boran called ‘Elephant destroying the building,’ a basic move where the elephant comes from below and picks up the building. So I incorporated some of these things into the film but of course with my own interpretations. With this basic movement (does more arm and fist maneuvers), the first part of this is to first show respect to the King (more postures later) and then to the elephant; some also do worship movements to the tusks. But in the end of course I added in my own stuff to make it more elegant and stylish. You see, in Muay Boran there is a lot of worshiping of things that are holy, and so there is holiness in the elephant. Yet the film shows what some bad people will do to the elephant and how far they will go to do it.”

It is really a reflection of the elephant’s fading shadow from the light of the Thai sun. Most of Thailand’s elephants were used for logging, yet because the land was over logged, the government banned the practice in 1989, forcing thousands of mahouts (elephant owners) and their expensive “pets” to move into the cities to beg for food and money. There, most elephants were kept in horrible conditions and became extremely undernourished. Elephant camps were then created outside the city where tourists arrived by bus loads to go on five-day elephant rides through the forest, not realizing that incessantly carrying basket loads of people on their backs can weaken and deform the elephant’s back. Mahouts ride on the back of the elephant’s neck, the strongest part of the elephant’s dorsal anatomy. Elephants at these camps are beaten, poked with sticks, and their legs are tied by rope until the skin is rubbed raw and their spirits are broken, all in the name of money. It is no wonder Jaa wants to give back to his childhood memories of Flower and Leaf and build an elephant sanctuary where abused and mistreated elephants can have a place to stay and live out the rest of their lives with the respect they deserve. So to Jaa, this journey starts with THE PROTECTOR.

Although it is difficult to imagine how one could lose a humongous elephant and her calf during a crowded festival without anyone seeing it, or how, when these behemoths are shipped to Australia, they are easily slipped through customs and end up in a Sydney restaurant, in THE PROTECTOR this happens. These two prized elephants were supposed to be given to the King of Thailand as tokens of devotion, but their protector Kham (Jaa) fails in his duties. With a heavy heart and armed with the courage, bravery and the fighting abilities of the Jaturungs, Kham travels to Australia in the name of all that is holy to Thai culture and Kham’s family heritage to rescue the elephants. Regardless of the suspect storyline, acting and screenplay structure, this $5.3 million film that took one year to shoot lives up to its Thai title of TOM YUM GOONG.

“Tom yum goong is a Thai dish, a soup,” Jaa says with a grin, “and most foreigners know about it. The dish is sweet, hot and spicy, and it represents Thailand. So the fight scenes are similar, intense, hot and spicy, thus the use of that Thai title.”

In a stroke of purposeful or inadvertent irony, Harvey Weinstein, under the moniker of The Weinstein Company, chose to change the Thai title to THE PROTECTOR. This not only reflects the theme of the film and the true historic nature of the Jaturungs, but as Jaa’s second film to get nationwide release in the States, it’s the same English title as Jackie Chan’s second Hollywood production released in 1985. The twist also goes as far as Jaa hiring a Jackie Chan impersonator to traipse by Kham as he arrives at Sydney Airport. Jaa giggles. “We could not afford the real one, but this one we could pay him with noodles.”

One person they were able to afford was Johnny Tri Nguyen, former member of the US National Wu Shu Team and the winner of two gold medals in forms and swordsmanship at the 1998 Pan-American Games. Fresh after working on SPIDERMAN 2 (2004) and matching wits with Spiderman as the Green Goblin double in SPIDERMAN (2002), Nguyen was asked to match body blows and blood with Jaa in THE PROTECTOR. I caught up with Nguyen who is currently completing his own culturally intense film in Vietnam called THE REBEL, which focuses on his nation’s heritage when, in the 1920s, Vietnam was under French Colonial rule.

One person they were able to afford was Johnny Tri Nguyen, former member of the US National Wu Shu Team and the winner of two gold medals in forms and swordsmanship at the 1998 Pan-American Games. Fresh after working on SPIDERMAN 2 (2004) and matching wits with Spiderman as the Green Goblin double in SPIDERMAN (2002), Nguyen was asked to match body blows and blood with Jaa in THE PROTECTOR. I caught up with Nguyen who is currently completing his own culturally intense film in Vietnam called THE REBEL, which focuses on his nation’s heritage when, in the 1920s, Vietnam was under French Colonial rule.

“The action used a similar approach,” Nguyen exclusively tells kungfumagazine.com, “and will incorporate high-impact Vietnamese martial arts, something that has never been done before and will be out later this year. So doing the same sort of intense action with Tony was a good preparation for the film.”

Nguyen embraced the philosophy underlying the fights on THE PROTECTOR, which was to do the action without CGI, wire and stunt doubles. This was a far cry from Hollywood. “In Hollywood picture fighting,” he says, “we have a practice called re-action. It’s basically a technique in which an actor plays out the pain of the fake contacts of the punches or kicks. In THE PROTECTOR, there was not much use for this practice. Fighting with Tony is a lot closer to what I have been training in a martial art studio than what I have been doing in the Hollywood film studios.

“One of the traditional martial arts I practice is an intense work of internal power and body armor. Knowing that I was going to fight the dude from ONG BAK, I brushed up on my good old kung fu. I’d also have to say this film’s biggest challenge was jump-kicking in cowboy boots and alligator skin pants. When I did manage to kick, I ripped the pants.” After a slight pause, he adds with a laugh, “Don’t try that at home.”

There are some marvelous sight gags, action set pieces and death-defying stunts in THE PROTECTOR – stuff we’ve all seen in ONG BAK, but presented in a different but just as effective flavor. Still, Jaa was determined to come up with something entirely new for this film. Partial inspiration was drawn from two movies: TIMECODE (2000), a film constructed from four continuous 90-minute takes; and RUSSIAN ARK (2002), in which a steadicam follows the main character around in a museum in one uninterrupted 96-minute shot.

“On this film,” Jaa explains, “we had the same crew as ONG BAK and so we were well-honed, more efficient and knew how to work together better. It was decided to do a fight scene more challenging and ambitious than ONG BAK, something that has never been done in any other martial art or action film. Thus was born the idea to do a four-minute fight sequence that was shot in one take, without any cuts or edits.

“In fact, the main inspiration of the fight came from Bruce Lee’s GAME OF DEATH, where Bruce goes up flights of stairs and fights on each floor.”

In THE PROTECTOR, Kham must fight his way up to the top floor of the film’s title restaurant to confront the vile villains responsible for kidnapping his elephants. Each floor was split into teams of stuntmen that were supposed to attack Jaa at the right moments. But of course in fight scenes where timing is everything, sometimes the clock did not strike midnight.

Jaa leans back, and with a boyish smile he says, “We did eight takes of this scene and could only do two per day because of all the preparation that went into it. We also had to change one of the steadicam operators because he couldn’t keep up with me running up the stairs. Even that one was really sucking wind toward the end of the fight.

“In one take, everything was perfect up until the third level, and just as I was going to throw out one of the stunt guys, the second team didn’t come out in time so we had to cut. Then there was another take, where everything was going well right up to the last and final fourth team of attackers and then we ran out of film. It was really frustrating, and of course everything had to be done in four minutes, but in the end it was worth it and it worked out pretty good.”

When asked what’s next and would he do this sort of thing again, he shakes his head. “I don’t think so. I’m now working on ONG BAK 2 and we really need to come up with something new and better for the film. It will use a lot more weapons and sword fights. As with all my films, the key to these movies is that I always want to show the world about Thai people, our culture, symbols, and to ultimately prove that we can make good films.”

Written by Dr. Craig Reid for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

© COPYRIGHT KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

All other uses contact us at gene@kungfumagazine.com.