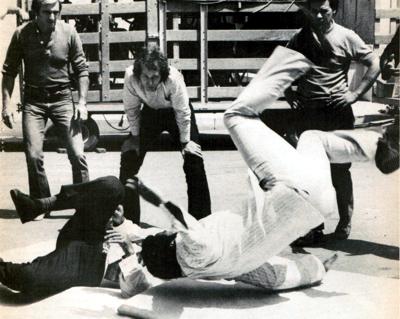

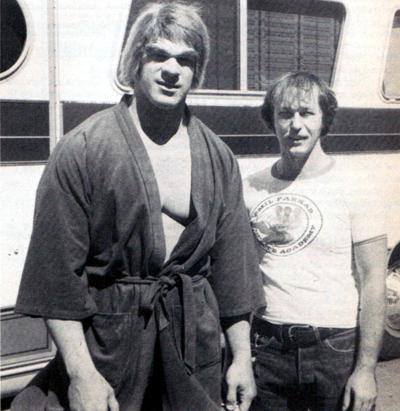

Fred Williamson, star of That Man Bolt, learns the strenuous art of falling

under the watchful eye of stunt choreographer Emil Farkas (Center)

“I haven’t done one piece of work of which I’m really proud,” says Emil Farkas, one of the veterans of stunt choreography, whose professional skills have added energy and impact to numerous television and motion picture productions.

This surprising admission stems from Farkas’ acute awareness of how little control the stunt choreographer actually has over what finally appears on the screen. Any fan who has ever been disappointed at the martial arts action in an American production, and has cursed at the inadequacies of the stunt choreographer should realize that the same stunt choreographer may well be sharing in the disappointment. In looking back over his experience in the industry, which stretch back to the screen debut of martial arts fight scenes in the late 60’s, Farkas can identify the specific constraints which limit and weaken the stunt choreographer’s art.

The initial restraints on martial arts action are firmly in place before the stunt choreographers even take on the project. The time and monetary limitation, the locale, the amount of violence allowable, and the actors involved set the parameters within which the stunt choreographer must work. Farkas explains each of these considerations,

“First, you have to know the time limitations-are you going to have 10 seconds, 20 seconds or 60 seconds for a fight scene. Then you find out about location. Naturally, you plan a fight differently if it is set outside or inside. Next, you ask about the monetary limitations. That basically come down to what I can wreck or can’t wreck. The more things you can break, the better your action will be.”

After taking into consideration these basics, Farkas next appraises the more subtle problem of the amount of violence which can be included in the movie. Over the years, Farkas has developed an almost intuitive sense for determing the exact quantity of broken bones, mangled flesh, and oozing blood which are acceptable for a television production, PG-rated movie, or R-rated movie. Farkas gave an impromptu example of how he would vary a scene for different violence levels. “Say the scene takes place in a restaurant. I’m sitting here with a woman and we’re lovers. Then the woman’s husband comes through the door. If the movie is to be R-rated, I throw the husband through the plate glass window. Or maybe I break a plate and cut him up. It’s bloody and messy, and the place is in shambles.

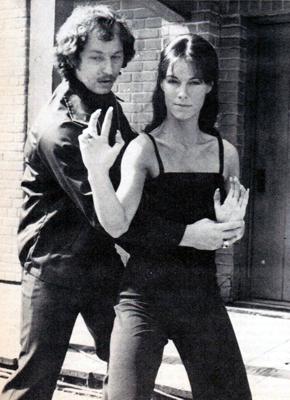

Farkas shows Spiderwoman star Joanna Cameron the proper hand position for a palm heel strike. Farkas insists on working with the star in his own school before any filming begins.

“If the film is PG-rated, I might kick his knee under the table, and the knee buckles. Then i hit him a few times, but there would be no close ups. His head hits the floor, and that finishes him up. That scene is much milder.”

The most vital element in planning a fight scene, and the one which has the most effect in determining its realism, is the actors and stuntpeople involved. “You have to know with whom you are working,” says Farkas. “If it’s an actor who’s a klutz, you use a different fight concept than if it’s for a athlete like Fred Williamson. Again you use a different concept if it’s someone like Benny Urquidez who can do anything you want him to.”

According to Farkas, the lack of trained martial arts actors is one of the biggest disadvantages of American movies. “The Chinese pictures all use martial arts stars. The choreographer is working with a guy who has done nothing but rehearse for ten years. In the U.S., you’re working with an actor who probably has never studied before.” Farkas tries to minimize the problem of having inexperienced leads. “I make a deal with the studio,” he says. “They have to give me a certain number of hours to work with the star beforehand, or I don’t do the picture. I need a minimum of five hours to coach the star at my school. It’s too difficult to go on a set with everyone trying to coach a guy who is nervous anyway. For That Man Bolt (1973) I gave Fred Williamson three weeks of lessons before he ever went on the set, and you could see the results.”

Although it is essential for the star to move with the appearance of expertise, most stunt choreographers agree that it is even more important to have stunt people who react to the techniques convincingly. Farkas complains, “The biggest problem is to convince stunt people that what sells the thing is how they look, how they react to the punch, not how the star looks. The Chinese are excellent at stunt work. The guys who end up on the receiving end look right, because they’re constantly working with each other all the time. Here in the U.S. the stunt choreographer ends up calling in ten guys who have no experience, and giving them a ten-minute lecture on how to take a punch and how to fall. That’s what Pat Johnson did when setting up the poolroom scene for Force Five (1981). Then he expected Richard Norton (the star in the scene) to go out into the poolroom and make the fight look good. It just doesn’t work.”

In the course of his lengthy career Farkas has choreographed scenes for numerous televisions actors including Chad Everette in In the Glitter Palace (1977) and Lou Ferrigno in The Incredible Hulk (1978).

In the course of his lengthy career Farkas has choreographed scenes for numerous televisions actors including Chad Everette in In the Glitter Palace (1977) and Lou Ferrigno in The Incredible Hulk (1978).

Farkas has one partial solution to the problem of an inadequate cast: constant practice. “You have to keep your people working all the time. I’d make them work until 3 a.m. every night if it was necessary. Repeat, repeat, repeat. By the time the scene rolls around, you have a better chance of having something decent.”

After having designed a fight scene and taking every advance precaution possible to make sure it will work, the stunt choreographer faces his next challenge: trying to bring his concept to life on the set and in front of the camera. The first difficulties occur in setting up the scene on location, where, in accordance with Murphy’s Law, anything that can go wrong usually does. “You envision the location one way and it’s always different,” Farkas says. “And then you have problems with the lighting and the camera angles. If the director is using one camera only, then all the punches and kicks have to come from one angle. If he has two or three, you’re freer to do different things.”

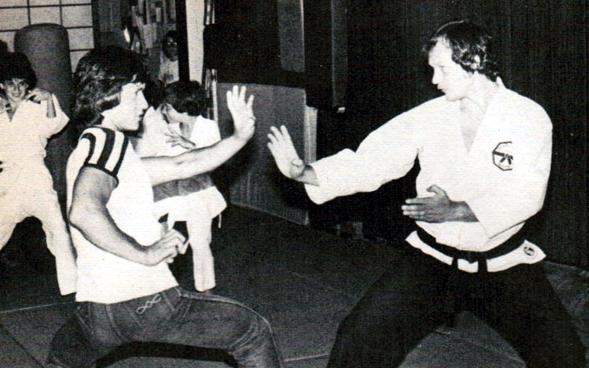

Farkas complains that the stunt choreographer of Chinese martial arts has an advantage, “He’s working with a guy who has done nothing but rehearse for ten years.” Here Farkas works out with one such accomplished star, Jacke Chan.

These are only minor difficulties, however. The real threat to the stunt choreographer’s careful plans appears on the set in a human form, that is, as the director of the film. Farkas explains why the stunt choreographer often comes to regard the director as his natural adversary. “The director is a layman. What looks terrible to you looks good to the director, and he doesn’t want to do a scene over eight times if that’s what it takes. He’ll say ‘Nah, that’s good enough. It’s too expensive to keep all these people hanging around.’ That’s why you have to try to get everything perfect beforehand. Here’s another place the Chinese have an advantage. The Chinese director is martial arts oriented, and knows what’s good.”

The combination of the director’s lack of sophistication and the actors’ lack of expertise causes most American stunt choreography to be conservative. “The American martial artists are new at the game, and they won’t take chances or do outrageous things the way the Chinese will,” Farkas says. “In all of Chuck Norris’ movies there’s not one memorable fight scene. The jump through the car window in Good Guys Wear Black (1978) is the greatest thing he’s ever come up with. Chuck is a terrific artists, but he’s afraid to take a chance.

At least on the set the stunt choreographer has the opportunity to communicate his point of view to the director. Once the film is in the editing room, however, the fight sequence is totally at the director’s mercy. Farkas says, “The director and editor will never ask the stunt choreographer in when they’re editing the film. Once in a blue moon they’ll show him the rushes and ask for his opinion. So it’s totally up to the discretion of the director, and I don’t know one director who is a martial arts expert. The director chops up the fight scene any way he pleases.

“To the American director, a fight scene is just another piece of action, no different than the action in a love scene with people rolling in bed. The director just wants to move the story along. In Force: Five (1981) they gave as much time for the helicopter huffing and puffing as they did for the fight scenes. The director thinks that all of those are action, and can be given as much time on the screen.”

Given this attitude, it is not surprising that directors will cut fight scenes into short, fast paced vignettes rather than allow the audience enough time to get involved in a particular fight. “Force: Five (1981) Benny Urquidez gets two hits and he’s gone.” Farkas says, “He’s wonderful, but the scene isn’t exciting.” Nor is it surprising that the directors won’t make any extra efforts to enhance the quality of the fight scenes, even though the results can be highly effective. Farkas recalls, “One of the reasons Billy Jack (1971) works so well is because Bong Soo Han had a relationship with Tom Laughlin (the producer/director) and could do what he wanted with the piece of film. When I saw the scene where Billy Jack says “I’m going to put this foot on the side of your face . . .’ and does that kick, I thought, “That Laughlin’s terrific!” Then I got the trailer of the film and slowed the kick down. They had synchronized the footage of Bong Soo Han so the scene starts with Laughlin and then Han does the actual kick. Most directors would never do that. They’d rather have a lousier kick than go to the time and energy to synchronize it. But these are the types of things that make a difference.”

The blame for choppy fight sequences cannot be totally given to the director and editor. Farkas believes that the American actors have to share part of the responsibility. “The actors have a hard time memorizing a minute routine. It is hard, with all the moves and punches involved. It’s easier to break up the scene into 10 or 15 second bits. The trouble is, it doesn’t look as good.

“In a Chinese picture, you have a long master shot (a shot that takes in all the action). You see the fighters going against each other hand against hand like fencers. The camera never stops, and you have a chance to really get into it. A good director would get one good master, and then in addition get a number of close-ups which zoom in and out.

“But this is hard for American Fighters. In Force of One (1979), the sparring between Bill Wallace and Chuck Norris looks real. It’s done in one long shot. That’s because they’re improvising, it’s real sparring. But as soon as the fighting starts, it gets choppy.”

The American martial arts movies which were successful – most notably Enter the Dragon (1973) – had longer, smoother fight scenes. In Farkas’ view, Bruce Lee’s ability to control the shooting of his scenes was essential to his success. “Bruce had control of the cameras. The only thing Bruce didn’t direct was the acting, but he directed the action totally. Robert Clouse had little to say. The scene with Bruce in the prison with the sticks – that scene took almost five minutes. By the end, the audience is exhausted. An American director would never allow it. In Force: Five (1981) it’s boom, boom, boom and they’re gone.”

Farkas emphasizes how important it is to let any tension-producing sequences – be it a fight scene, a chase scene, or a horror scene – have enough time to develop and strain the audience to the utmost. “For example, The Warriors (1979) was one two-hour chase,” he says. “The director had the idea of making the whole film a chase from one end of New York to the other. It almost never lets up, and the audience is so caught up that it walks out tired.

“Bruce Lee realized that this worked, and he knew how to milk a great action for all it was worth, not just make it short and choppy. In Chinese pictures, the fight scenes are long and drawn out. You have a chance to get into it. You don’t get 90 fights. You can have a great picture with three fights that are long enough to exhaust you, and the audience walks away having gotten their money’s worth.

According to Farkas, the build-up to a scene can be as important as the action. “Here’s the greatest concept of action ever put on film. It’s from a samurai movie. Two men are confronting each other. The camera is at three quarters shot, from the knees up. Neither of them move. Thirty seconds go by. You hear the howling of the wind. Sixty seconds go by. Two minutes go by. I saw the film three times and I timed it, so I know this is right. Nothing happens. Three minutes go by. Nothing happens, and you’re going nuts. Three and a half minutes go by . . . and nothing. Four minutes go by. The men haven’t blinked the camera hasn’t moved. You hear a buzz. The camera moves in, and you see a fly. One of the men’s eyes shift to the fly. The other man’s sword comes out and as the eyes of the first man returns, the sword has swung around and cut off his head. The sword goes back to the scabbard, and you see the head roll off. It took five minutes to do a two-second scene. That’s the difference. That’s the sort of scene Bruce Lee would have come up with.”

Farkas want to be able to make the sort of movie that would take these risks, and has come to the logical conclusion: he wants to produce and direct his own martial arts film. He is currently in the planning stages for a project which will pit expert martial artists against such renown bodybuilders as Franco Columbu or Arnold Schwarzenegger. “Could you see a guy like Benny Urquidez walk into Gold’s Gym (a Southern California gymnasium known for training some of the world’s most famous bodybuilders) and take on 35 of the largest muscle men in the world?” Farkas asks. “A fight like that would last ten minutes on the screen, and I’ll guarantee you that everyone will want to see it. No short quickies in this movie. It’s not how many fights you do, but how exciting I can make them that will count.”

Will a great stunt choreographer be able to create a great martial arts movie? If a movie uses the promise of martial arts action as its special selling point, it seems reasonable to assume that fight scenes of higher quality, in terms of technical excellence and cinematic excitement, should make the film more attractive to the ticket buying public. The production of films based on this premise, by experts such as Emil Farkas, will at least give the American audience the chance to judge martial arts movies which more fully exploit the possibilities of the genre.

By Sandra Segal in Martial Arts Movies, October 1981